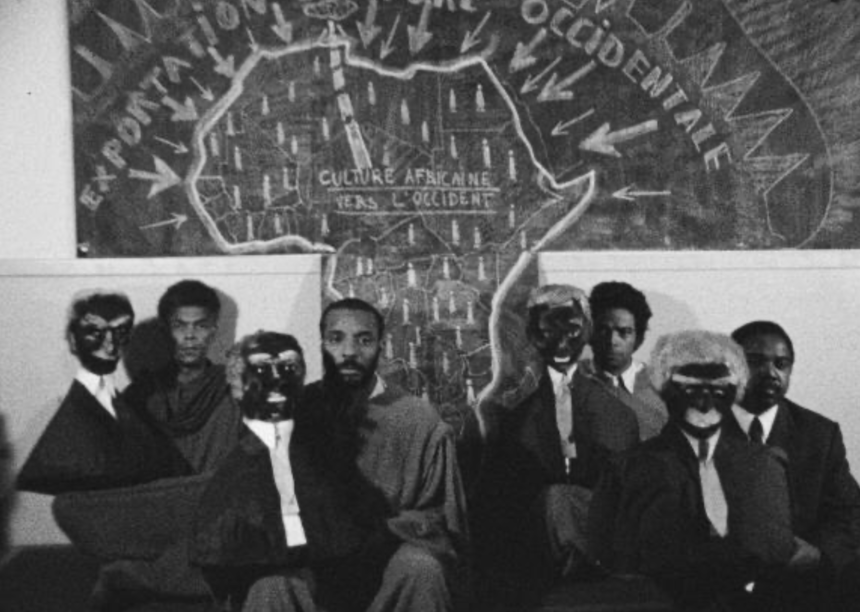

Throughout the world when people use the term cinema all refer more or less consciously to a single cinema, which for more than half a century has been created, produced, industrialised, programmed and then shown on the world’s screens: Euro-American cinema.

This cinema has gradually imposed itself on a set of dominated peoples. With no means of protecting their own cultures, these peoples have been systematically invaded by diverse, cleverly articulated cinematographic products. The ideologies of these products never ‘represent’ their personality, their collective or private way of life, their cultural codes, or of course the least reflection of their specific ‘art’, their way of thinking, of communicating — in a word, their own history… their civilisation.

The images this cinema offers systematically exclude the African and the Arab.

It would be dangerous (and impossible) to reject this cinema as simply alien — the damage is done. We must get to know it, the better to analyse it and to understand that this cinema has never really concerned the African and Arab peoples. This seems paradoxical, since it fills all the cinemas, dominates the screens of all African and Arab cities and towns.

But do the masses have any other choice? ‘Consuming’ at least fifty films in a year, how many films does the average African see that really talk to him?

Is there a single one which evokes the least resonance, the least reflection of his people’s life and history — past, present and future? — Is there a single image of the experiences of his forefathers, heroes of African and Arab history? Is there a single film inscribed in the new reality of co-operation, communication, support, and solidarity of Africans and Arabs?

In Lawrence of Arabia an image of Lawrence — not of the Arabs — is disseminated. In Gentleman of Cocodie a European is the gentleman hero, and not an Ivory Coast African.

This may seem exaggerated — some will say that at least one African country, Egypt, produces some relatively important films each year… that since independence in African countries a number of cineastes have made a future for themselves. In the whole continent of Africa, Egypt is only one country, one cultural source, one sector of the market — and few African countries buy Egyptian films. They produce too few films, and the market within Egypt is still dominated by foreign films.

African and Arab film-makers have decided to produce their own films. But despite their un- doubted quality they have no chance of being distributed normally, at home or in the dominant countries, except in marginalised circuits — the dead-end art cinemas.

Even a few dozen more film-makers producing films would only achieve a ratio of one to ten thousand. An everyday creative dynamic is necessary for a radical change in the relationship between the dominant Euro-American production and distribution networks and African and Arab production and distribution, which we must control.

Only in this way, in a spirit of creative and stimulating competition between African and Arab film-makers, can we make artistic progress and become ‘competitive’ on the world market. We must first control our own markets, satisfy our own peoples’ desires to liberate their screens, then establish respectful relations with other peoples, and balanced exchange.

WE MUST CHANGE THE HUMILIATING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DOMINATING AND DOMINATED, BETWEEN MASTERS AND SLAVES.

Some flee this catastrophic state of affairs, thinking cinema restricted for Western, Christian and capitalist elites… or throwing a cloak of fraternal paternalism over our film-makers, ignoring and discrediting their works, blaming them, in the short term forcing them to a formal and ethical ‘mimesis’ — imitating precisely those cinemas we denounce — in order to become known and be admitted into international cinema; in the end forcing them into submission, renouncing their own lives, their creativity and their militancy.

Since the independence of our countries a sizeable number of our film-makers have proved their abilities as auteurs. They encounter increasing difficulties in surviving and continuing to work, because their films are seldom distributed and no aid is forthcoming.

Due to the total lack of a global cultural policy, African and Arab cinema is relegated to being an exotic and episodic sub-product, limited to aesthetic reviews at festivals, which, although not negligible, are undoubtedly insufficient.

Each year millions of dollars are ‘harvested’ from our continents, taken back to the original countries, then used to produce new films which are again sent out onto our screens.

50% of the profits of multinational film companies accrue from the screens of the Third World. Thus each of our countries unknowingly contributes substantial finance to the production of films distributed in Paris, New York, London, Rome or Hong Kong.

They have no control over them, and reap no financial or moral benefit, being involved in neither the production nor the distribution. In reality, however, they are coerced into being ‘co-producers’. Their resources are plundered.

The United States allows less than 13% foreign films to enter its market — and most of these are produced by European subsidiaries controlled by the U.S. majors. They exercise an absolute protectionism.

Most important is the role of the cinema in the construction of peoples’ consciousnesses.

Cinema is the mechanism par excellence for their everyday social behaviour, directing them, diverting them from their historic national responsibilities. It imposes alien and insidious models and references, and without apparent constraint enforces the adoption of modes of behaviour and communication of the dominating ideologies. This damages their own cultural development and blocks true communication between Africans and Arabs, brothers and friends who have been historically united for thousands of years.

This alienation disseminated through the image is all the more dangerous for being insidious, uncontroversial, ‘accepted,’ seemingly inoffensive and neutral. It needs no armed forces and no permanent programme of education by those seeking to maintain the division of the African and Arab peoples — their weakness, submission, servitude, their ignorance of each other and of their own history. They forget their positive heritage, united through their forefathers with all humanity. Above all they have no say in the progress of world history.

Dominant imperialism seeks to prevent the portrayal of African and Arab values to other nations; were they to appreciate our values and behaviour they might respond positively to us.

We are not proposing isolation, the closing of frontiers to all Western film, nor any protec- tionism separating us from the rest of the world. We wish to survive, develop, participate as sovereign peoples in our own specific cultural fields, and fulfill our responsibilities in a world from which we are now excluded.

The night of colonialism caused many quarrels among us; we have yet to assess the full consequences. It poisoned our potential communications with other peoples; we are forced into relations of colonial domination. We have only preconceived and false ideas of each other imprinted by racism. They believe themselves ‘superior’ to us; they are unaware of our peoples’ roles in world history.

Having been colonised and then subjected to even more pernicious imperialist domination, if we are not entirely responsible for this state of affairs, some intellectuals, writers, film-makers, thinkers, our cultural leaders and policy-makers are also responsible for perpetuating this insatiable domination.

It has never been enough simply to denounce our domination, for they dictate the rules of their game to their own advantage. Some African and Arab film-makers realise that the cinema alone cannot change our disadvantaged position, but they know that it is the best means of education and information and thus of solidarity.

It is imperative to organise our forces, to re-assert our different creative potentialities, and to fill the void in our national, regional and continental cinemas. We must establish relations of communication and co-operation between our peoples, in a spirit of equality, dignity and justice. We have the will, the means and the talent to undertake this great enterprise.

Without organisation of resources we cannot flourish at home, and dozens of African and Arab intellectuals, film-makers, technicians, writers, journalists and leaders have had to leave their countries, often despite themselves, to contribute to the development and overdevelopment of countries that don’t need them, and that use their excesses to dominate us.

This will continue until we grasp the crucial importance of this cultural and economic strategy, and create our own networks of film production and distribution, liberating ourselves from all foreign monopolies.

“What is Cinema for Us?” was first published under the name Abid Mohamed Medoun Hondo in Framework (Issue 11, autumn 1979) in a translation by Greg Kahn and reprinted in a slightly edited version in Jump Cut, no. 31, March 1986, pp. 47–48. Reprint with friendly permission from the author.